The Power of Habit

I read this book exactly 2 years ago. As I mentioned in my post on Losing 70+ Pounds over a year from a year ago, this book motivated me a lot to think through habit design. There are three main sections in this book: The habits of individuals, the habits of successful organizations and the habits of societies. I’ll quickly review each of the three.

The Habits of Individuals

This was, by far, my favorite section. Knowing how habits work is the first step to designing them. This section starts off with the Habit Loop. It is a three step loop that consists of the trigger (or cue), the routine and finally, the reward. A trigger tells our brain to go into automatic mode, and which routine to follow. Our brain is always trying to do as less as possible, and chunks multiple actions into routines that we go through without giving any thought. The reward that follows reinforces the habit loop, and tells the brain that the routine is working and is well worth remembering.

Triggers can be created, and they work despite having nothing to do with the routine. In early 20th century, 7%(!) of the American population used to brush their teeth. Claude Hopkins, a marketing genius, convinced everyone that if they run their tongue over their teeth, they will notice a thin film which makes their teeth look off-color and leads to decay. Although this film is naturally occurring and this claim is downright false, the trigger was effective enough that within a decade, toothpaste usage had grown to 65%.

One of the easier ways to change a habit is to substitute the routine and keep the trigger and reward parts intact. So if you want to cut down on coffee and want to take up running, instead of reaching for your kettle next time you feel drowsy, put on your running shoes and go for a quick run. The endorphins will take care of the rest.

Some habits are not able to form because they lack a reward. Adding a reward and completing the loop may be the key in such cases. Coming back to the toothpaste example above, the author later argues that Pepsodent succeeded not because of the trigger, but because it was the first toothpaste to provide a reward for brushing your teeth: they included citric acid, mint oil and other ingredients that create the familiar cool, tingling effect.

This section is full of great case studies— from how Alcoholics Anonymous really works to how Tony Dungy changed the game of American Football by training his team members to not think during the play, but react based on habits learned around certain cues.

The Habits of Successful Organizations

Some habits are more important than others — they set off a chain reaction of habit disruption. These are called keystone habits and are critical both for organizations and individuals. The book talks about how Paul O’Neill, the new CEO of Alcoa, made workplace safety number one priority for the company by requiring that every unit president had to report any workplace accident to him, along with a plan to make sure it never happened again, within 24 hours of the accident. This one requirement set off a cascade of improvements throughout the reporting lines in the company, and vastly improved not just the workers’ safety, but also increased Alcoa’s income by 500% over the following decade.

Willpower is the most important habit, and it can be strengthened over time. Organizations that work on this outperform almost every other competitor. Here are three ways to strengthen your willpower:

- Do something that requires a lot of discipline. Train for a marathon. Start a strict diet regimen. Idea is to constantly practice delayed gratification — willpower can be strengthened like a muscle.

- Plan ahead for worst-case scenarios. Mentally rehearse what you would do in case things don’t work out the way you think they should.

- Preserve your autonomy — as far as possible, put yourself in a situation where you choose what you have to do next. If you’re constantly assigned tasks by others, your willpower will drain faster. Look out for micro-managers, and find a way to distance yourself from them.

Crises can be important and pivotal moments for organizations to change their habits. Never underestimate the power of a good crisis:

A company with dysfunctional habits can’t turn around simply because a leader orders it. Rather, wise executives seek out moments of crisis — or create the perception of crisis — and cultivate the sense that something must change, until everyone is finally ready to overhaul the patterns they live with each day.

Sandwiching a new routine between two existing routines is another powerful way to build a new habit. This is frequently employed by companies and organizations to sell us stuff. An example I liked: radio stations have long sandwiched a new song between two popular familiar songs to create one hit after another: in truth, people care more about familiarity than quality, and are more likely to like a new song if it sounds familiar to something they already love. I started noticing this myself lately after I started carefully analyzing tracklists of weekly radio shows from my favorite music labels.

The Habits of Societies

I liked this section for I got to learn a bit about Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, which eventually led to the Civil Right Act of 1964. The boycott became a new social habit which led to larger social habits of peaceful protests, which in turn jump started the Civil Rights movement. It was the first successful boycott in part due to a large number of Mrs. Parks’ weak ties across the African-American community:

People who hardly knew Rosa Parks decided to participate because of a social peer pressure — an influence known as “the power of weak ties” — that made it difficult to avoid joining in.

In The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell also argues that weak ties are more important than our close friends since they are numerous and expose us to different groups and opportunities than the ones we would already be aware of.

In particular, one story from the book stuck with me over the years:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’

And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes ‘What the hell is water?’

The water is habits, the unthinking choices and invisible decisions that surround us every day — and which, just by looking at them, become visible again.

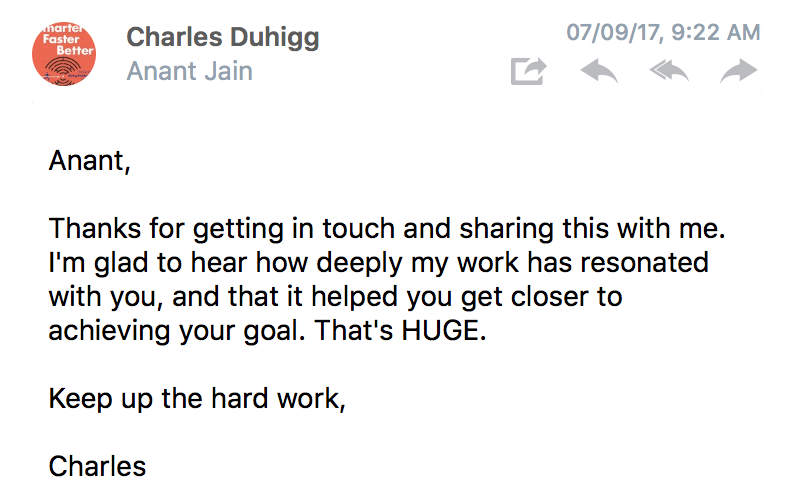

At times, some books change your lives so tangibly that you feel you should shoot a note to the author to thank them for helping you get the snowball rolling. You know you’ll never hear anything back since nobody has the time to reply to fan mail. Not in this case:

The best time to read this book was 6 years ago when it came out. The second best time is now. Here’s the Amazon Smile link.

This is #11 in a series of book reviews published weekly on this site.